11.2. Defining Classes¶

In Python, every value is actually an object. Whether it be a a list, or an integer, they are all objects. Programs manipulate those objects either by performing computation with them or by asking them to perform methods. To be more specific, we say that an object has a state and a collection of methods that it can perform. The state of an object represents those things that the object knows about itself.

We’ve already seen classes like str, int, and float.

These were defined by Python and made available for us to use.

However, in many cases when we are solving problems we need to create

data objects that are related to the problem we are trying to solve.

We need to create our own classes.

As an example, consider the concept of a mathematical point. In two

dimensions, a point is two numbers (coordinates) that are treated

collectively as a single object. Points are often written in

parentheses with a comma separating the coordinates. For example,

(0, 0) represents the origin, and (x, y) represents the point

x units to the right and y units up from the origin. This

(x, y) is the state of the point.

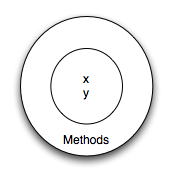

Thinking about our diagram above, we could draw a point object as

shown here.

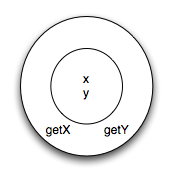

Some of the typical operations that one associates with points might

be to ask the point for its x coordinate, getX, or to ask for its

y coordinate, getY. You may also wish to calculate the distance

of a point from the origin, or the distance of a point from another

point, or find the midpoint between two points, or answer the question

as to whether a point falls within a given rectangle or circle. We’ll

shortly see how we can organize these together with the data.

Now that we understand what a point object might look like, we can

define a new class. We’ll want our points to each have an x

and a y attribute, so our first class definition looks like this.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 | class Point:

def __init__(self: Point) -> None:

self.x: float

self.y: float

self.x = 0.0

self.y = 0.0

return None

|

Class definitions must appear near the beginning of a program, after

the import statements, but before any other code. The syntax rules

for a class definition are the same as for other compound

statements. There is a header which begins with the keyword,

class, followed by the name of the class, and ending with a colon.

Every class should have a method with the special name __init__.

This initializer method, often referred to as the constructor,

is automatically called whenever a new instance of Point is

created. It gives the programmer the opportunity to set up the

attributes required within the new instance by giving them their

initial state values. The self parameter is automatically set to

reference the newly-created object that needs to be initialized.

So let’s use our new Point class now.

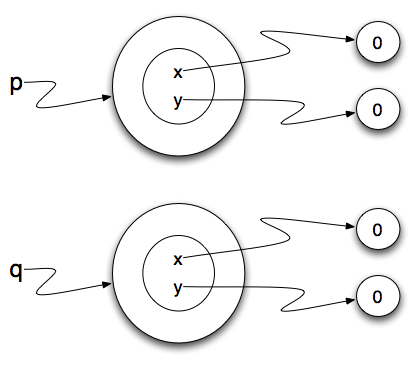

During the initialization of the objects, we declared two attributes called x and y for each, and gave them both the value 0.0.

Note

The asignments are not to x and y, but to self.x and

self.y.

The attributes x and y are always attached to a

particular instance.

The instance is always explicitly referenced with dot notation.

You will note that when you run the program, nothing happens. It

turns out that this is not quite the case. In fact, two Points

have been created, each having an x and y coordinate with value 0.0.

However, because we have not asked the point to do anything, we don’t

see any other result.

You can see this for yourself, via codelens:

(chp13_points)

The following program adds a few print statements. You can see that

the output suggests that each one is a Point object.

The variables p and q are assigned references to two new

Point objects. A function like Point that creates a new

object instance is called a constructor. Every class

automatically uses the name of the class as the name of the

constructor function. The definition of the constructor function is

done when you write the __init__ function.

It may be helpful to think of a class as a factory for making objects. The class itself isn’t an instance of a point, but it contains the machinery to make point instances. Every time you call the constructor, you’re asking the factory to make you a new object. As the object comes off the production line, its initialization method is executed to get the object properly set up with its factory default settings.

The combined process of “make me a new object” and “get its settings initialized to the factory default settings” is called instantiation.