5. User-controllable objects

So far you can create a Pygame window, and render a ball that will fly across the screen. The next step is to make some bats which the user can control. This is potentially far more simple than the ball, because it requires no physics (unless your user-controlled object will move in ways more complex than up and down, e.g. a platform character like Mario, in which case you'll need more physics). User-controllable objects are pretty easy to create, thanks to Pygame's event queue system, as you'll see.

5.1. A simple bat class

The principle behind the bat class is similar to that of the ball class. You need an __init__ function to initialise the ball (so you can create object instances for each bat), an update function to perform per-frame changes on the bat before it is blitted the bat to the screen, and the functions that will define what this class will actually do. Here's some sample code:

class Bat(pygame.sprite.Sprite):

"""Movable tennis 'bat' with which one hits the ball

Returns: bat object

Functions: reinit, update, moveup, movedown

Attributes: which, speed"""

def __init__(self, side):

pygame.sprite.Sprite.__init__(self)

self.image, self.rect = load_png('bat.png')

screen = pygame.display.get_surface()

self.area = screen.get_rect()

self.side = side

self.speed = 10

self.state = "still"

self.reinit()

def reinit(self):

self.state = "still"

self.movepos = [0,0]

if self.side == "left":

self.rect.midleft = self.area.midleft

elif self.side == "right":

self.rect.midright = self.area.midright

def update(self):

newpos = self.rect.move(self.movepos)

if self.area.contains(newpos):

self.rect = newpos

pygame.event.pump()

def moveup(self):

self.movepos[1] = self.movepos[1] - (self.speed)

self.state = "moveup"

def movedown(self):

self.movepos[1] = self.movepos[1] + (self.speed)

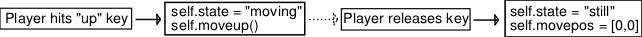

self.state = "movedown"As you can see, this class is very similar to the ball class in its structure. But there are differences in what each function does. First of all, there is a reinit function, which is used when a round ends, and the bat needs to be set back in its starting place, with any attributes set back to their necessary values. Next, the way in which the bat is moved is a little more complex than with the ball, because here its movement is simple (up/down), but it relies on the user telling it to move, unlike the ball which just keeps moving in every frame. To make sense of how the ball moves, it is helpful to look at a quick diagram to show the sequence of events:

What happens here is that the person controlling the bat pushes down on the key that moves the bat up. For each iteration of the main game loop (for every frame), if the key is still held down, then the state attribute of that bat object will be set to "moving", and the moveup function will be called, causing the ball's y position to be reduced by the value of the speed attribute (in this example, 10). In other words, so long as the key is held down, the bat will move up the screen by 10 pixels per frame. The state attribute isn't used here yet, but it's useful to know if you're dealing with spin, or would like some useful debugging output.

As soon as the player lets go of that key, the second set of boxes is invoked, and the state attribute of the bat object will be set back to "still", and the movepos attribute will be set back to [0,0], meaning that when the update function is called, it won't move the bat any more. So when the player lets go of the key, the bat stops moving. Simple!

5.1.1. Diversion 3: Pygame events

So how do we know when the player is pushing keys down, and then releasing them? With the Pygame event queue system, dummy! It's a really easy system to use and understand, so this shouldn't take long :) You've already seen the event queue in action in the basic Pygame program, where it was used to check if the user was quitting the application. The code for moving the bat is about as simple as that:

for event in pygame.event.get(): if event.type == QUIT: return elif event.type == KEYDOWN: if event.key == K_UP: player.moveup() if event.key == K_DOWN: player.movedown() elif event.type == KEYUP: if event.key == K_UP or event.key == K_DOWN: player.movepos = [0,0] player.state = "still"

Here assume that you've already created an instance of a bat, and called the object player. You can see the familiar layout of the for structure, which iterates through each event found in the Pygame event queue, which is retrieved with the event.get() function. As the user hits keys, pushes mouse buttons and moves the joystick about, those actions are pumped into the Pygame event queue, and left there until dealt with. So in each iteration of the main game loop, you go through these events, checking if they're ones you want to deal with, and then dealing with them appropriately. The event.pump() function that was in the Bat.update function is then called in every iteration to pump out old events, and keep the queue current.

First we check if the user is quitting the program, and quit it if they are. Then we check if any keys are being pushed down, and if they are, we check if they're the designated keys for moving the bat up and down. If they are, then we call the appropriate moving function, and set the player state appropriately (though the states moveup and movedown and changed in the moveup() and movedown() functions, which makes for neater code, and doesn't break encapsulation, which means that you assign attributes to the object itself, without referring to the name of the instance of that object). Notice here we have three states: still, moveup, and movedown. Again, these come in handy if you want to debug or calculate spin. We also check if any keys have been "let go" (i.e. are no longer being held down), and again if they're the right keys, we stop the bat from moving.