Lab 7 In-Class: More Selection

Lab Objectives

- Introduce the switch statement

- Work with boolean expressions

- Practice writing conditional statements

- Witness and dissect a basic event-driven program

|

As usual, create a subdirectory for the lab, open up the Web version of

this handout in Mozilla Firefox, and open Eclipse.

The Switch Statement

The Java switch statement (p. 231 - 234) is

another conditional statement.

Switch provides a compact, efficient syntax that is useful when you

would otherwise have a cascading if statement in which each

condition checks the value of the same expression. For example, the

if and switch statements below do the same thing -- either could be used

as shown in the program:

System.out.println("Enter size box you want");

int boxSize = scan.nextInt();

double price;

if (boxSize == 10)

{

System.out.println("Small");

price = 2.5;

}

else if (boxSize == 20)

{

System.out.println("Medium");

price = 3.75;

}

else if (boxSize == 30)

{

System.out.println("Large");

price = 5.0;

}

else

{

System.out.println ("Not a valid size.");

price = -1;

}

|

switch (boxSize)

{

case 10:

System.out.println("Small");

price = 2.5;

break;

case 20:

System.out.println("Medium");

price = 3.75;

break;

case 30:

System.out.println("Large");

price = 5.0;

break;

default:

System.out.println ("Not a valid size.");

price = -1;

}

|

if (price > 0)

System.out.println("Price is $" + price);

else

System.out.println("Sorry, we don't have that size");

A few things to note about switch statements:

- The expression you are switching on (boxSize in the example above)

must have an integer or character value (an example with char values

is on page 231). It cannot be a boolean,

floating point, or object.

- The expression is evaluated once and then is matched against

each of the cases, starting at the top. When a case matches, all the

rest of the code including later cases is executed. However,

very often

you will only want to execute the code for a single case. To do this, put a

break statement after the code for that case; this will

break control out of the switch statement, sending it to the

next statement in the program.

- If no other case matches, default always matches (like else

in an if statement).

You will use a switch statement (as well as a nested if) in the next exercise.

Exercise #1: Rock, Paper, Scissors

Program Rock.java contains a skeleton for the

game Rock, Paper, Scissors. Open it and save it to your lab7 directory.

Add statements to the program as indicated by the comments so that the program

asks the user to enter a play, generates a random play for the computer,

compares them and announces the winner (and why). For example, one run

of your program might look like this:

Enter your play (R, P, or S): r

Computer play is S

Rock crushes scissors, you win!

Note that the user should be able to enter either upper or lower case

r, p, and s. The user's play is stored as a string to make it easy to

convert whatever is entered to upper case (use a method of the String class).

Use a switch statement to convert the randomly generated integer for

the computer's play to a string (the statement is started for you).

When your program works, modify it so that if either the user or the

computer does not have a legal play (R,P,S), it prints a message

telling which is wrong (user or computer)

and terminates without playing the game.

(Of course, if the computer's play is illegal that means your statement

that generates the random number is wrong! -- for this exercise, you should

still check)

If both plays are ok,

go ahead and print the computer's (legal) play and give the

winner. Think about the condition for this: the user's play

should be R or P or S; if it's not

one of these, there's a problem. You can use similar reasoning

for the computer's play.

So the structure of the last part of your program should now

look like this:

...

switch statement to translate the computer play to a string

if (the computer's play is illegal)

print message

else if (the person's play is illegal)

print message

else

{

print computer play

the nested if ... else ... to determine and print winner

}

Be sure your program is properly indented. Remember that Eclipse will

format your code using CTRL-SHIFT-F.

Print your completed program to turn in.

Exercise #2: Date Validation

Computers use dates all the time. For example, a program that keeps

keeps track of your bank account may need your birth date;

a program that keeps track of books in a library must

deal with due dates; or the college radio station WRKE may need a

program to generate

a random "WRKE Super Prize Birthday" (remember Lab 3?). An object-oriented

program that works with dates would have a class to represent a date

and an important part of the class would be to make sure the date is

a valid one (remember generating dates such as 2/30 as a WRKE birthday?).

In this exercise you will write a class that represents a date. A date

has three attributes - day, month, and year - which need to be represented

by instance variables. The class has two constants to define the

range of years for a valid date (currently a valid year is from 1000 to

2050, inclusive). The methods will include the standard ones we

should include in most classes (a constructor and a toString method),

several needed for making sure the date is valid, and one that will

advance the date to the next day.

A skeleton of the Date class

is in Date.java. We will use a simple

program TestDates.java to test the methods

in the Date class as we write them.

Save these files to your lab7 directory.

Do the following to complete the Date class and the program:

- Notice that the instance variables START_YEAR and END_YEAR are defined as

public int . As it stands, this means that they are visible outside

the class, and (*gasp*) they can be modified outside the class. The first

part is useful; it might be valuable for a programmer to have access to those

numbers. The second part is horrific - imagine the chaos that would come

about if programmers were allowed to change the END_YEAR on a whim. Fix this

problem. Your solution should a) allow a client programmer to see these values

b) prevent the client programmer from changing these values and c) not include

any additional methods.

- In the validDate method in the Date class add the following

as indicated by the comments (ignore the comment about valid

day for now) in the program:

- An assignment statement that sets monthValid to true if the

month entered is between 1 and 12, inclusive, and false otherwise.

- An assignment statement that sets yearValid to true if

the year is between START_YEAR and END_YEAR, inclusive.

- Change the return statement (which currently just returns true)

to return true if the month and year are valid (and false otherwise).

Note that your return statement should just return a boolean

expression (avoid using an if).

- In TestDates.java do the following (as indicated by the comments):

- Write a statement that instantiates the someDay object.

- Write an if statement that prints either a "Date is valid" or

"Date is not valid" message. You need to invoke the validDate

method of the Date class.

- An important part of programming is verification . This

means that you are examining your output to make sure that your results are

valid.

The sheet "Testing the Date Class" will be used to record the

dates you use for testing the date class. Note that it gives

a set of 5 dates to use to test to see if your program is

checking the month correctly. Pay attention to the choice of

test dates - errors frequently crop up in programs at the

"boundaries" of data ranges. In this case the correct range for

the month is 1 to 12, inclusive, so 4 of the test cases are

at the boundaries (one date just inside and one just outside).

Run the TestDates program 5 times

entering each of the 5 dates. Indicate whether or not

your program correctly identified the date as valid or not

(you can just put a check mark for correct or an X for incorrect).

Of course, if your program was incorrect for any date fix it! Retest any

incorrect dates and add a check mark if you corrected the mistake

(leave your X - you won't be penalized for it!).

- Now test your program to see if it is correctly identifying valid

years. Fill in the blanks with 5 dates that would be good for

testing the years - three valid dates and two that are not. Run

your program for those dates and record the results. Fix any

problems you identify.

- Add a method boolean leapYear() to the Date class that

returns true if the year

is a leap year. Here is the leap year rule: A year is

a leap year if a) it's divisible by 400, or b) it's

divisible by 4 and it's not divisible by 100. Your leapYear

method should have a single return statement that returns the boolean

condition describing a leap year (no if!).

- In TestDates.java, add a condtion that tests valid dates to see if

they are a leap year. Print out an appropriate message

(is/is not a leap year).

- When setting out to verify that your program works with leap years, we

might consider eight possible conditions that need to be checked (3 boolean

expressions with 2 outcomes each: 2^3 = 8). However, you will find that

because the boolean expressions are not independent, some of the condtions

can't be expressed (e.g. If a year is divisible by 400, it has to be

divisible by 4) On the test sheet, identify the eight conditions and determine

which are viable and which are impossible.

For all of the viable conditions, provide

an example date and then verify that your program provides the correct answer.

Fix any problems.

- In the daysInMonth method in the Date class

add an if statement that

determines the number of days in the month

and stores that value in variable numDays. If the month

entered is not valid, numDays should get 0. Note that to figure out

the number of days in February you'll need to check if it's a leap year

(that is, you will need to call the leapYear method).

- In the validDate method add an assignment statement to set

dayValid to true if the day is a valid day in the given month

(the day would need to be between what two values?).

- Modify the return statement in validDate

to return a boolean expression that is true if the date is valid.

- Run TestDates to test your latest changes.

To verify your program completely, you should check the boundary conditions

for all the months. In the interest of time for this lab, you need to test

the boundary conditions for February and record them on your sheet.

- Complete the toString method in the Date class

by completing the switch

statement that assigns a name to the month and change the return

statement to return a string for the date in the standard way we

write dates (for example, October 25, 1996).

- Modify the print statements in TestDates to print the Date

object (implicitly using toString) along with the message. For

example, if the date entered is 3, 2, 1993 the message should be

"March 2, 1993 is a valid date." but if 3, 32, 1993 is entered

the message should be "March 32, 1993 is not a valid date."

- Add a method void advance() in the Date class that advances the date

to the next day (so, for example, if the date is currently February 28, 2006

the date is advanced to March 1, 2006).

- Now modify TestDates to test the advance method. In particular,

inside the if statement already there

and after your if that checks for a leap year,

add a statement to advance the date and then

a statement to print the advanced date (appropriately labeled).

- How should you test the advance method?

Given that you have verified most of your program already, it is probably a

good idea to try a few random dates and then think of any important boundary

conditions. Verify your program with at least three intermediate dates and

then identify two critical boundary conditions to test. Make sure that you

justify your selection of the boundary condtions on the sheet.

Run your program on your test cases and record the results.

Correct any problems.

Print both Date.java and TestDates.java to turn in.

Exercise #3: GUI Events

This exercise is desgined to provide a very elementary introduction to GUI

events.

The file HelloButtonPanel.java contains

a class that defines a GUI panel that contains a button and a label. When

the button is pushed, the text of the label changes to display a greeting.

Study this code and make sure you understand how it functions.

The file GUIGreet.java is a simple driver for this

panel (i.e. it creates a frame for the panel and displays it). Save the two

files to your lab7 directory and then run GUIGreet.java and click the

button to see what the GUI looks like. Examine the code in HelloButtonPanel.java

to be sure you understand where the components of the GUI come from

and where the code to print the hello message is.

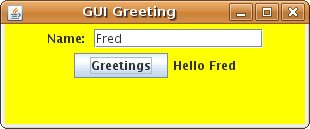

Modify the HelloButtonPanel class as follows:

- Include a JTextField (see the section on JTextFields starting on

page 195). Note: you should add the JTextField

to the panel before you add the JButton to make sure that it is

placed to the left of the button. Your JTextField should be able to hold 15

characters.

- Add a new JLabel that reads "Name:" to the panel

(to the left of the JTextField).

- When the button is pushed, the program should concatenate the text,

"Hello " with the text in the JTextField.

When the program is run, and the button is pushed, your GUI should look

something like:

Print your updated version of HelloButtonPanel to hand in.

What to Hand In

- Printouts of Rock.java, Date.java, TestDates.java, and

HelloButtonPanel.java plus your "Testing the Date Class" sheet of the

dates you used to test the Date class.

- Tar up your lab7 directory and e-mail it to your instructor at roanoke.edu.

Put cpsc120 lab7 in the subject line.